In a previous post, I used the phrase “scripted curriculum” to describe EL and Odell, two literacy curricula that have been adopted for English language arts courses at all levels in the district where I live and work. When I’ve used the phrase in conversation with some educators, they’ve protested: “It’s not a script.” So I’d like to spend a little time breaking down why I use that phrase and how implementation decisions might successfully lead to culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy (“informed pedagogical improv,” if you will,) and less of the blind script-following from which district leaders (and probably the curriculum companies themselves) rightly distance themselves.

I call them scripts because they are written to model teacher talk.

I don’t know of any curriculum companies that advertise themselves as “scripted,” but I do know elementary teachers in previous districts where I have worked who have been told that in the first year of teaching a new literacy curriculum, they need to “follow the script.”

I call lesson plans like these scripts because, although they may not always be written in script format like a drama or screenplay, they are written in language that could be easily read aloud to students, with the “you” referring to students and with text features like quotation marks, bolding, italics, or colored text to delineate teacher talk. Here are some examples EL’s 8th grade unit about Latin American folklore (focused on Summer of the Mariposas by Guadelupe Garcia McCall) and Odell’s 11th grade unit about Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns.

You can examine lesson plans on these websites after making an account.

EL’s read-aloud vocabulary scripts

There are scripted questions that teachers can ask while reading aloud and unpacking difficult vocabulart. The page number and quotations are referents, the bold text is what the teacher asks, and the italics are what the students should say in response.

| page 131 “. . . into the brush.” Why do the girls stop driving? What do they encounter? The car breaks down. They encounter a woman who invites the girls to her house for something to drink. page 137 “. . . justice would prevail.” What do the Federales say about the girls and the dead man in the news segment? They say the dead man was a drug dealer and fugitive and his murderers may have kidnapped the Garza girls. |

EL’s close reading note-catcher scripts

This script is from a “close reading” activity in which students read a nonfiction article for background. There are serveral bullet points to explain the purpose of the lessons to teahers, and then there is a step-by-step script for each paragraph or section of the reading and discussion. In this section they simply use quotation marks to show what teachers should say.

| Invite students to reread the first sentence of paragraph 4 and the main idea given in the right-hand column of their note-catchers. (Note: this sentence is so full of hard words that the main idea continues to be given—it would take too long for students to try to figure it out.) Guide students to understand resilience—you could use a tennis ball to demonstrate. Ask: “How is the main idea of this section related to the heading of the section?” (The main idea answers the question in the section heading by describing what is in the tales. Specifically, it talks about how to bounce back and cope with hardships and difficult situations.) Ask: “What are some of the details or examples the author uses to support the idea that ‘folktales teach about how to bounce back and cope with hardships’?” Refer to the Close Reading note-catcher provided for sample responses. Guide students in adding supporting details to their note-catchers. Ask: “Why might this aspect of the folktales be so important to Latin American people?” Refer to the Close Reading note-catcher provided for sample responses. Discuss: “How does this section support the central idea that Latin American folktales help people understand their own concerns?” (Answers will vary. Encourage students to support observations with specific evidence from the text.) |

There are also scripted “language dives”

| · Remind students about the first step in the Deconstruct stage: “When we do a Language Dive, first we read the sentence. We talk about what we think it means and how it might help us understand our guiding question.” · Invite students to put their finger by these sentences from Summer of the Mariposas on their note-catcher: “La Llorona said we have to remain noble and kind. If we do that, everything will be all right. · Read aloud the sentences twice, and then ask students to take turns reading the sentences aloud with their partners. · Say: “What do these sentences mean to you?” (Responses may vary. Encourage and acknowledge all responses.) “How do these sentences add to your understanding of the theme: being kind and pure of heart can help people live fuller, more meaningful lives?” (Responses will vary.) · Say: “In this Language Dive, we are going to look at the second sentence, ‘If we do that, everything will be all right,’ but you will need to think about the meaning of the first sentence, ‘La Llorona said we have to remain noble and kind, to help you understand the second one.” · Read aloud the sentence, together, twice: “If we do that, everything will be all right.” · After inviting responses, write and display students’ ideas. |

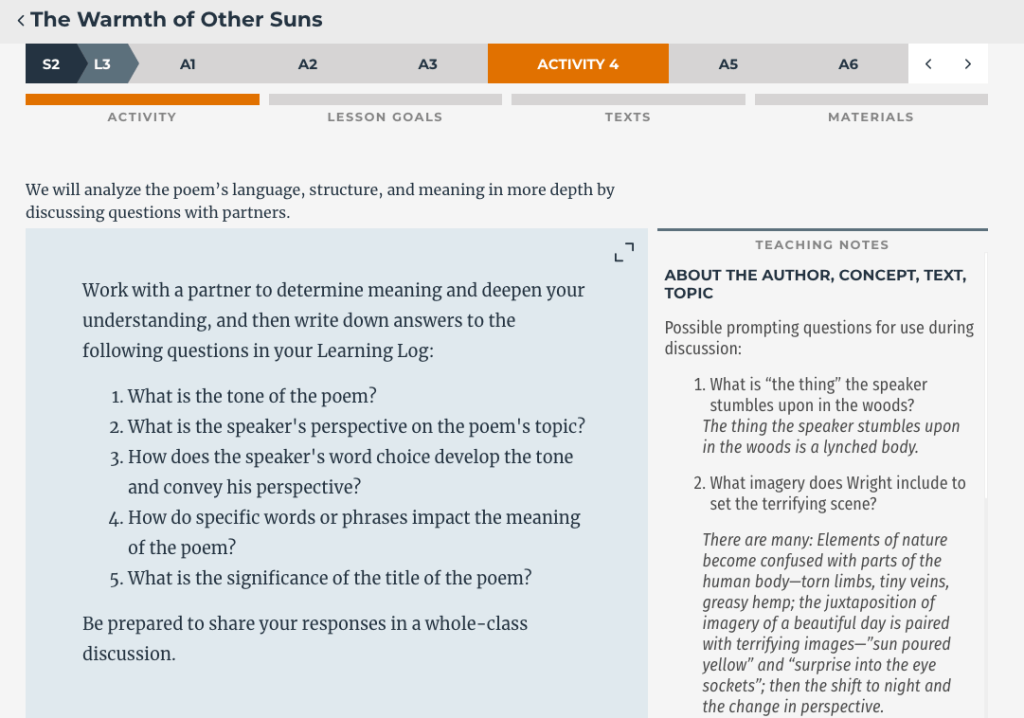

Odell’s discussion of a poem

Odell’s approach to scripting is a little different. On their website, they feature a blue box on the left side that includes student-facing language and “Teacher notes” for more detail along the right side. Like EL, Odell includes additional questions and possible student answers in differently formatted text.

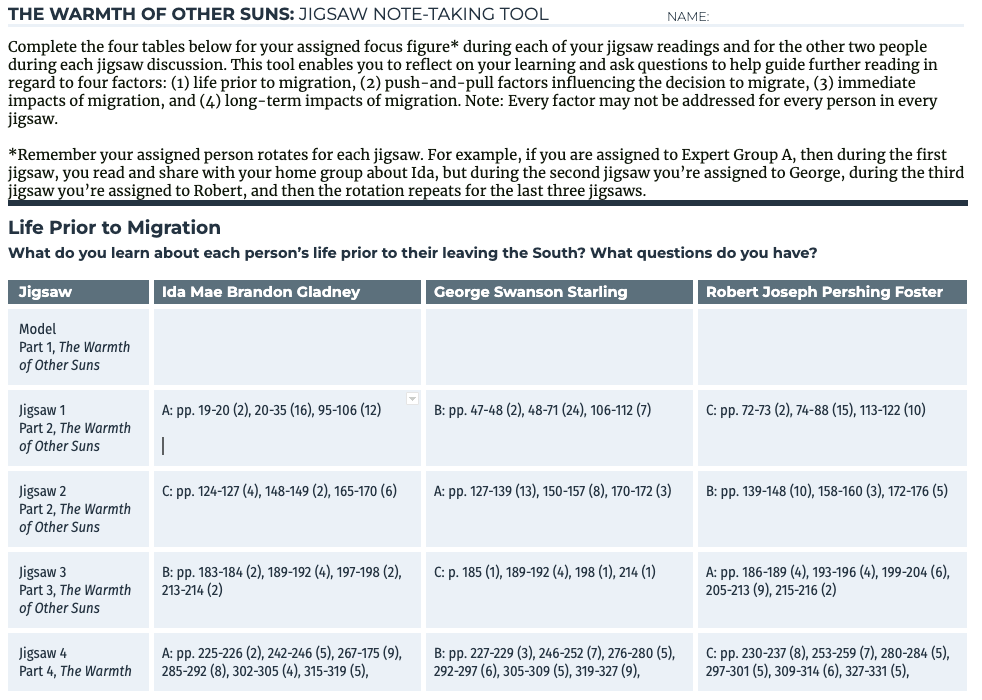

Odell’s small group jigsaw discussion

Odell also relies on handouts and graphic organizers with detailed instructions to further “script” discussions and activities for students and teachers. EL uses this strategy as well, and although the handouts from both companies are usually editable, they are often very detailed and text-heavy, like this one that provides tiny spaces for students to record their thoughts (or they could type and the boxes will expand).

But what might it look like to go “off-script”? (Answers may vary.)

I have never met any administrators or curriculum consultants who say they want teachers to read scripted lessons to students. But I have not heard any administrators or curriculum consultants seriously consider or model what the experience of transforming the very detailed teacher language and materials shown above into a lesson—one that is aligned with the scripted lesson’s goals but that also is responsive to students identities and current lived experiences. You can’t script those, and it can be scary and overwhelming for educators who work at systems levels to think about maintaining district or school-wide coherence while also embracing the individuality and autonomy of both teachers and students.

After I finished my doctoral program, I began teaching 8th grade in my current district, just as it was adopting the EL literacy curriculum. At one point, I cried when I stacked up all the teacher’s guides and thought about how much time it might take me to read and understand the purpose of each lesson, each graphic organizer, and each suggested question. I felt exhausted and demoralized—and a more than little bit scared not to follow the script.

Yes, it was my 19th year in education and my 12th as an English language arts eductor. Yes, I had been part of three different curriculum development and implementation processes in previous districts. Yes, I had spent three years working with school library leaders across the country to plan for the implemention of new standards for school librarians. Yes, I had recently published a peer-reviewed article critiquing scripted lesson plans published by a renowned international education journal. And yes, I had been working with preservice teachers and inservice teacher graduate students who I supported in analyzing literature, curating texts, and planning units and lessons with authentic, rigorous assessments.

But it didn’t matter. Faced with hundreds of pages of lesson plans and materials that seemed to said, “We know how you should teach,” and “these step-by-step instructions printed on official-looking documents trump your knowledge and experience,” my confidence plummeted. I wasted hours deciphering the intraciacies of lesson plans, assessments, and supplemental materials, trying to imagine how they would work in my online teaching environment during the fall of 2020. I wasted hours searching for what was so special or perfect about these lessons that merited so much attention—attention that took me away from attending to my students.

In the end, I made the choice to put the teacher’s guides on the bottom shelf to collect dust because I simply did not have time to spend reading the scripts and “implementing with fidelity.” It was September of 2020 and the world was falling apart, and I had to spend the majority of my time just trying to get to know my students, to get them to speak with me and with their peers, to understand the challenges they were facing while learning online, and to engage them in literacy in a meaningful way that would speak to their lives in the current moment.

So I became what Eisenback (2020) would call something between a “negotiator” and a “rebel.” For the most part, I stayed aligned with the standards and the broader topics dictated by EL, and I used some of their assessments and texts as inspirations or options for my students. At one point I used an assessment adapted pretty closely to EL’s performance task, and in others I kept the genre and goals the same, while opening up the texts and options for analysis. But overall, I increased choice, curated current texts that spoke to our context, and revised assessments to focus on what students were most interested in.

It wasn’t perfect by any means, but it kept me focused on the humans who, as Emdin reminds us in Rachetdemic, mattered most: my students and me.

Missing from the script: Students’ identities

In a previous post, I pulled excerpts from educational literature by Black, indigenous, and scholars of color I’ve read this summer that includes direct critiques of scripted curriculum—often because such scripts fail to engage students in making connections to their own lives. The literary anlaysis questions featured above are purely text-based and they do not invite students to make connections to their lives, identities, or cultures. I didn’t go looking for technocratic questions—that’s the vast majority of what you’ll find in EL and Odell lesson plans. These are important, of course, since analysis of language and structure are important parts of literary analysis.

However, writers don’t write books and poems in order to show off their prowess with metaphors or their ability to weave together multiple plotlines. No, their primary goals are usually about portraying the human condition in way that speaks to other humans. So why aren’t there any questions in these scripts about how the poem evokes feelings, memories, or connections? Why don’t Odell or EL ever invite students to begin with a reaction and then probe the text—and themselves—more deeply to understand where that reaction might have come from?

I’ll address this in more detail in another post, but for now, suffice it to say that most commercial and OER curriculum materials align with a New Critical approach to literary analysis, and the scripted lessons that result are stuffed so full of technocratic literary analysis that there is little room for students’ questions, ideas, reactions, emotions, or connections. When a 45-minute lesson is already scripted to include 5-10 brief activities, it can be overwhelming for teachers to first, digest the pages and pages of instructions and materials and then, think about which to prioritize and which to condense or elimate in order to make room for more identity-foucsed, student-focused work.

My bottom line (for now)

For me, whether or not a curriculum developer or administrator calls it a “script” or not, when I see language that simulates or models what students will say to teachers, I’ll keep calling it a scripted curriculum.

That doesn’t preclude a district adopting a program like EL or Odell while also providing rigorous, critical, supportive professional development about how to maintain a focus on their students’ identities while taking advantage of the pre-made resources and the potential for alignment across teachers and schools. It’s possible, but it’s much more difficult than just purchasing the materials, handing them out, and communicating to teachers about pacing guides and assessment plans.

This year, I look forward to being part of the hard but essential of work starting with student identities rather than scripts when designing and implementing curriculum. Stay tuned.

Leave a comment